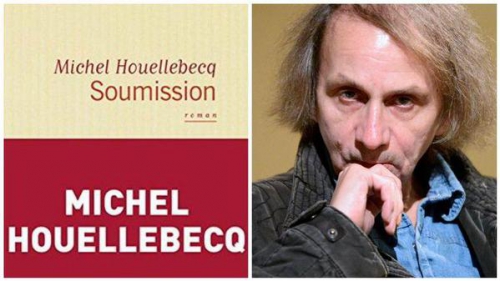

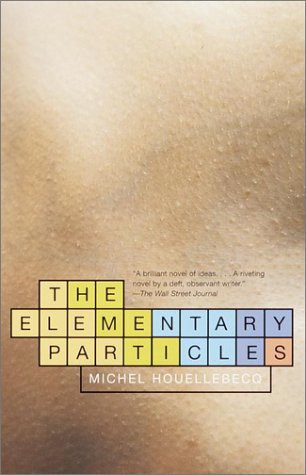

MICHEL HOUELLEBECQ : «L’ISLAMOPHOBIE N’EST PAS UNE FORME DE RACISME»

Interview pour La Nación, Buenos Aires

Sylvain Bourmeau

Ex: http://metamag.fr

L’auteur des “particules élémentaires” a, de nouveau, mis le doigt dans la plaie, avec un livre de fiction qui aborde le futur de la France et le rôle de l’Islam. Soumission, son sixième roman, se déroule en 2022. La France vit dans la peur. Le pays est agité à cause de mystérieux problèmes. Les médias, volontairement, occultent la violence urbaine quotidienne. Tout est étouffé, le public est laissé dans l’obscurité et, en quelques mois, le chef d’un parti musulman récemment crée est élu président. La nuit du 5 juin, lors d’une segonde élection, la première ayant été annulée pour fraude caractérisée, Mohammed Ben Abbes sort vainqueur face à Marine Le Pen grâce à l’appui tant de la gauche que de la droiteLe lendemain, les femmes abandonnent les vêtements occidentaux. La majorité commence par utiliser de grandes tuniques de coton au-dessus de leurs pantalons ; réagissant positivement aux indications du gouvernement, elles quittent massivement leurs emplois. Le chômage masculin baisse rapidement du jour au lendemain. Dans les quartiers autrefois dangereux les crimes deviennent rares. Les universités adoptent la référence islamique. Les professeurs qui ne se convertissent pas en signe de soumission au nouveau régime n’ont d’autre possibilité que la retraite anticipée.

La Naciòn : Pourquoi l’avez vous écrit ?

Michel Houellebecq :Pour diverses raisons. En premier lieu, c’est tout simplement mon travail, quoique le mot ne me plaise pas. J’ai observé de grands changements lorsque je suis revenu m’installer en France, quoique ces changements ne soient pas spécifiquement français mais occidentaux en général. La seconde raison est que mon athéisme n’a pas survécu à la quantité de morts auxquels j’ai été confronté. De fait, cela a commencé à me paraître insoutenable.

La mort de votre chien, de vos parents ?

Oui, ce furent beaucoup de choses en peu de temps. Un élément est peut-être que, contrairement à ce que je pensais, jamais je ne fus totalement athée. J’étais agnostique. Normalement, ce qualificatif sert de paravent à l’athéisme, mais cela ne me paraît pas être exact dans mon cas. Au vu de tout ce que je sais aujourd’hui, lorsque je réexamine la question de l’existence ou non d’un créateur, d’un ordre cosmique, ce genre de choses, je me rends compte que ma seule certitude est de ne pas avoir de réponse.

Comment définiriez-vous ce roman ?

L’expression de politique fiction n’est pas mal. Je ne pense pas avoir lu beaucoup de romans du même type, parfois j’en ai lu, mais plus dans la littérature anglaise que française.

A quelles œuvres pensez-vous ?

A certains livres de Conrad ou de John Buchan. A des ouvrages plus récents aussi, des thrillers, mais pas aussi bons. Un thriller peut se dérouler dans un cadre politique, pas seulement dans le monde des affaires. Mais il existe une troisième raison à la rédaction de ce roman : j’aimais la manière dont il débutait. J’écrivis la première partie, jusqu’à la page 26, d’un trait. Je la trouvais très convaincante, car il m’est très facile d’imaginer un étudiant rencontrant un ami dans le personnage de Huysmans auquel il dédie alors sa vie. Cela ne m’est pas arrivé. J’ai lu Huysmans beaucoup plus tard, lorsque j’avais quasiment 35 ans je crois, mais vraiment il m’aurait beaucoup plu de le lire. Je crois qu’il aurait été pour moi un véritable ami. De sorte qu’après avoir rédigé ces 26 pages, je n’ai plus rien fait de quelques temps. C’était en janvier 2013 et j’ai repris le texte cet été. Mais à l’origine le projet était différent. Il n’allait pas s’appeler Soumission ; le premier titre était La Conversion. Dans le projet originel, le narrateur se convertissait aussi mais au Catholicisme. Ce qui signifie qu’un siècle après Huysmans, il suivait la même voie, puisque Huysmans abandonne le naturalisme pour devenir catholique. Mais j’ai été incapable de réaliser le projet.

Pourquoi ?

Ça ne collait pas. Selon moi, la scène essentielle du livre se trouve au moment où le narrateur jette un œil à la Vierge Noire de Rocamadour, ressent un pouvoir spirituel, un peu comme des vagues, et soudain elle disparaît dans le passé et lui retourne au parking, seul et désespéré.

Le livre est-il un roman satirique ?

Non. Sincèrement, il est possible qu’une petite partie du livre se moque des journalistes politiques et des hommes politiques aussi. Mais les personnages principaux ne sont pas ridiculisés.

D’où tenez-vous l’idée d’une élection présidentielle en 2022 dont les protagonistes seraient Marine Le Pen et le chef d’un parti musulman ?

Marine Le Pen me paraît une candidate plausible pour 2022 et peut-être même pour 2017. Le parti musulman c’est différent. Là se trouve le noyau dur du problème, là se trouve la vérité. J’ai essayé de me placer du point de vue d’un musulman et me suis rendu compte qu’ils étaient dans une situation totalement schizophrénique. En général, les musulmans ne s’intéressent pas aux thèmes économiques. Leurs préoccupations sont plutôt sociétales. Sur ces questions ils se situent très loin de la gauche et des verts. Il suffit de penser au mariage homosexuel pour comprendre ce que je veux dire. Mais cela s’applique à une grande quantité d’autres thèmes. On ne voit pas non plus de raisons pour qu’ils votent en faveur de la droite, ou de l’extrême droite qui n’en veut pas. Aussi, lorsqu’un musulman veut voter, qu’est-il censé devoir faire ? La vérité est qu’il se trouve dans une situation impossible. Il n’a aucune représentation. Ce serait une erreur de dire que sa religion n’a aucune conséquence politique. En réalité il y en a. Il y en a aussi pour les catholiques même si ces derniers ont été plus ou moins marginalisés. Pour toutes ces raisons il me paraît que l’idée d’un parti musulman est très réaliste.

Mais de là à imaginer qu’un parti de ce type puisse être en mesure de gagner des élections présidentielles dans 7 ans…

Je suis d’accord, ce n’est pas très réaliste. Pour deux raisons, en réalité. D’abord, et cela est le plus difficile à imaginer, les musulmans devraient apprendre à s’entendre entre eux. Pour cela, il faudrait quelqu’un d’extrêmement intelligent et doté d’un immense talent politique, qualités que je prête à mon personnage Ben Abbes. Mais un talent extraordinaire, par définition, est rare. Et même en supposant que ce personnage existât et que le parti montât en puissance, cela demanderait plus de 7 ans. Si on observe l’action des frères musulmans, on constate des réseaux régionaux, des œuvres sociales, des centres culturels, des lieux de prière, des centres de vacances, des services de soins, quelque chose qui ressemble à ce qu’avait fait le parti communiste. Je dirais que dans un pays où la pauvreté se répand, ce parti pourrait attirer des gens au-delà du musulman “moyen” si je peux l’appeler ainsi, puisqu’en réalité il n’existe pas aujourd’hui de musulman moyen depuis qu’on observe la conversion à l’Islam de personnes qui ne sont pas d’origine nord-africaine. Mais un processus de ce type demanderait plusieurs décennies. Le sensationalisme des médias joue en réalité un rôle négatif. Par exemple, ils ont aimé l’histoire du "type" qui vivait dans un village de Normandie, qui était “de souche”, qui ne venait pas d’une famille décomposée et qui s’est converti puis est parti en Syrie pour participer à la guerre sainte. Il est raisonnable de penser que pour chaque "type" qui se comporte ainsi il s’en trouve des douzaines d’autres qui ne font rien de semblable. Après tout, on ne fait pas la guerre sainte pour s’amuser, cela ne concerne que les individus qui sont suffisamment motivés pour exercer la violence, ce qui signifie qu’il s’agit simplement d’une minorité.

On pourrait aussi prétendre que ce qui les intéresse n’est pas la conversion mais le fait d’aller en Syrie.

Je ne suis pas d’accord. Je crois qu’un Dieu est nécessaire et que le retour de la religion n’est pas un slogan mais une réalité qui progresse clairement.

Cette hypothèse est fondamentale pour le livre, mais on sait que de nombreux “chercheurs” la dédaignent depuis des années, affirmant avoir démontré que nous assistons en réalité a une sécularisation progressive de l’Islam et que la violence et la radicalisation doivent s’analyser comme les derniers instants de l’islamisme. C’est le type d’affirmation que l’on trouve chez Olivier Roy et chez d’autres individus qui s’intéressent à cette question depuis plus de 20 ans.

Ce n’est pas ce que j’ai observé, quoi qu’en Amérique du Nord et du Sud l’islam ait moins prospéré que les sectes évangélistes. Ce n’est pas un phénomène français, c’est global. Je ne connais pas le cas de l’Asie, mais celui de l’Afrique est intéressant car il y a là deux puissantes religions en progrés : le christianisme évangélique et l’islam. Sur beaucoup de points je reste un disciple d’Auguste Comte et ne crois pas qu’une société puisse survivre sans religion.

Mais pourquoi avoir pris la décision de raconter ces choses d’une manière dramatique tant exagérée tout en reconnaissant que la thèse d’un président musulman en 2022 est peu réaliste ?

Cela doit être mon côté production pour un marché de masses, ma dimension Thriller.

Vous ne l’appelleriez-pas votre côté Eric Zemmour ?

Je ne sais pas, je n’ai pas lu son livre

Lui et quelques autres écrivains se recoupent, malgré leurs différences, et décrivent une France contemporaine qui me paraît fantaisiste, dans laquelle la menace de l’Islam se resserre sur la société française. Cela constitue aussi un de vos principaux éléments. La trame de votre roman, me semble-t-il, l’accepte comme hypothèse et promeut une description de la France contemporaine semblable à celle qui ressort du travail de ces intellectuels.

Je ne sais pas, je connais seulement le titre du livre de Zemmour [ Le Suicide français ] et cela ne correspond pas du tout à ma manière de voir. Je ne crois pas que l’on assiste au suicide de la France. Je crois que ce à quoi l’on assiste est pratiquement le contraire. L’Europe se suicide mais, au milieu de l’Europe, la France tente désespérément de survivre. C’est quasi l’unique pays qui lutte pour survivre, le seul dont la démographie lui permette de survivre. Le suicide a une cause démographique. C’est la meilleure manière de se suicider et la plus efficace. Justement, la France ne se suicide absolument pas. Je dirai même que la conversion est un signal d’espérance, et non une menace. Cela dit, il ne me semble pas que les personnes se convertissent pour des raisons sociales ; les raisons de se convertir sont plus profondes, y compris le fait que mon livre me contredise légèrement, puisque Huysmans reste le paradigme de l’homme qui se convertit pour des raisons purement esthétiques. En réalité, les questions qui préoccupent Pascal laissent Huysmans de marbre. Il ne les mentionne jamais. Cela me coûte même d’imaginer un esthète de ce type. Pour lui, la beauté était la preuve. La beauté d’une rime, d’un tableau, de la musique prouvait l’existence de Dieu.

Cela nous ramène à la question du suicide, étant donné que Baudelaire a déclaré à propos de Hysmans que le seul choix à sa portée était le suicide ou la conversion.

Non, celui qui a émis ce commentaire est Barbey d’Aurevilly, et cela avait du sens, surtout après avoir lu À rebours. Je l’ai relu avec attention et, finalement, si, il est chrétien. C’est troublant.

Pour reprendre le problème de vos exagérations peu réalistes, vous décrivez dans le roman, sous une forme vague et floue, divers phénomènes mondiaux, cependant le lecteur ne sait jamais exactement ce qu’ils sont. Cela nous entraîne dans le monde de la fantaisie, n’est-ce-pas ? vers la politique de la terreur.

Oui, peut-être. Oui, le livre possède un côté terrible. J’utilise les tactiques de l’angoisse.

Comme celle qui consiste à imaginer une situation où l’Islam s’empare du pays ?

En réalité, on ne sait pas avec clarté de quoi on devrait avoir peur, si ce sont des autochtones ou des musulmans. J’ai laissé la question ouverte.

Est-ce que vous vous êtes demandé quel pourrait être l’effet d’un roman construit sur cette hypothèse ?

Néant. Absolument aucun effet.

Vous ne croyez pas qu’il va conforter l’image d’une France que je viens de décrire, celle où l’islam est suspendu sur notre tête comme une épée de Damoclés, comme la possibilité la plus horrible?

De toutes manières les médias ne parlent pas d’autres choses, ils ne pourraient pas en parler plus. Il est impossible de parler de cela plus qu’ils ne le font, de telle sorte que mon livre n’aura aucun effet.

Vous n’avez pas envie d’écrire sur un autre thème afin de ne pas vous joindre à la meute ?

Non, une partie de mon travail consiste à parler de ce dont tout le monde parle, objectivement. J’appartiens à mon époque.

Vous prétendez dans votre roman que les intellectuels français cherchent à éviter de se sentir responsables, mais vous êtes-vous demandé quelle était votre responsabilité comme écrivain ?

Mais je ne suis pas un intellectuel. Je ne prends pas parti et ne défends aucun régime. Je renonce à quelque responsabilité que ce soit, je réclame l’irresponsabilité totale, sauf lorsque je donne mon opinion sur la littérature, alors oui je m’engage comme critique littéraire. Mais ce sont les essais qui changent le monde.

Les romans non ?

Bien sûr que non. Quoique je soupçonne le livre de Zemmour d’être réellement trop long. Je crois que le Capital de Marx est bien trop long. En réalité, ce qui s’est lu et a changé le monde, c’est le Manifeste Communiste. Rousseau a changé le monde, parfois il sait comment toucher directement les points clefs. C’est simple. Si vous voulez changer le monde, il faut dire comment il est réellement et ce qu’il convient de faire pour le changer. On ne peut se perdre en considérations romanesques. C’est inefficace.

Mais il ne manquerait plus que je dise comment utiliser un roman en tant qu’instrument épistémologique. Ce fut le thème de “La carte et le territoire”. Dans ce livre vous avez adopté des catégories pour décrire, des oppositions, qui sont plus que douteuses. C’est le type de catégories employées par les éditeurs de Causeur, par Alain Finkielkraut, Eric Zemmour ou Renaud Camus. Par exemple, l’opposition entre l’antiracisme et le sécularisme.

On ne peut nier qu’il y ait là une contradiction.

Je ne la vois pas. Au contraire, les mêmes personnes sont souvent à la fois antiracistes militantes et ferventes défenseurs du sécularisme, les deux plongeant leurs racines dans les lumières.

Voyez, les lumières sont mortes, qu’elles reposent en paix. Un exemple parlant ? La candidate de gauche du parti de Besancenot portait le voile. Voilà une contradiction. Mais seuls les musulmans sont en réalité dans une situation schizophrénique. Au niveau des valeurs, les musulmans ont plus de point commun avec la droite qu’avec la gauche. L’opposition est bien plus fondamentale entre un musulman et un athée qu’entre un musulman et un catholique. Cela me paraît évident.

Mais je ne comprends pas le lien avec le racisme.

Tout simplement parce qu’il n’y en a pas. Si on parle objectivement, il n’y en a pas. Quand je suis passé en jugement pour racisme et que finalement j’ai été acquitté, il y a maintenant une dizaine d’années, le juge a correctement conclus que la religion musulmane n’est pas un attribut racial. Cela, aujourd’hui, est devenu plus évident. De telle sorte que la portée du mot racisme a été étendue pour inventer le délit d’islamophobie.

Peut-être le mot était-il mal choisi, mais il existe des manières de stigmatiser des groupes ou des catégories de personnes, qui sont des formes de racisme.

Non, l’islamophobie n’est pas une forme de racisme. Si quelque chose est devenu évident aujourd’hui, c’est bien cela.

L’islamophobie sert d’écran à un type de racisme qui ne peut plus s’exprimer aujourd’hui à cause de la loi.

Je crois que c’est faux. Tout simplement. Je ne suis pas d’accord.

Vous utilisez une autre dichotomie douteuse, l’opposition entre l’antisémitisme et le racisme, quand en réalité nous pouvons déceler diverses époques durant lesquelles les deux choses étaient liées.

Je crois que l’antisémitisme n’a rien à voir avec le racisme. Il se trouve que je cherche à comprendre l’antisémitisme depuis longtemps. A première vue, on est tenté de le relier au racisme. Mais de quel racisme parlons-nous lorsqu’une personne ne peut pas deviner si quelqu’un est juif ou ne l’est pas parce que la différence est invisible ? Le racisme est plus élémentaire que tout cela, il s’agit d’une différence de couleur de peau.

Non, parce que le racisme culturel existe depuis longtemps chez nous.

Mais alors vous demandez aux mots de signifier des choses qu’ils ne veulent pas dire. Le racisme est simplement le fait qu’une personne ne nous plaise pas parce qu’elle appartient à une autre race, parce qu’elle n’a pas la même couleur de peau, ou les mêmes traits, etc. On ne peut élargir le mot pour lui donner une autre signification.

Mais puisque du point de vue biologique les races n’existent pas, le racisme est nécessairement culturel.

Mais le racisme existe, apparemment, de partout. Il est évident qu’il a existé depuis le moment où les races ont commencé à se mélanger. Soyez honnête! Vous savez très bien qu’un raciste est quelqu’un qui n’apprécie pas une autre personne parce qu’elle a la peau noire ou une tête d’arabe. Le racisme c’est cela.

Ou à cause de ses valeurs ou de sa culture.

Non, c’est un problème différent. Désolé.

Parce qu’il est polygame par exemple.

Ah mais quelqu’un peut-être scandalisé par la polygamie sans être raciste du tout. Cela doit être le cas de beaucoup de gens qui ne sont pas du tout racistes. Mais revenons à l’antisémitisme car nous avons dévié. Puisque personne n’a jamais pu deviner si quelqu’un est juif à partir de son aspect ou de son mode de vie, étant donné que lorsque l’antisémitisme s’est développé, peu de juifs menaient une vie réellement juive, que pourrait signifier l’antisémitisme? Ce n’est pas une forme de racisme. Tout ce qu’il faut faire, c’est lire les textes pour se rendre compte que l’antisémitisme n’est rien de plus qu’une théorie de la conspiration : des gens dans la coulisse sont responsables de toutes les difficultés du monde, ils conspirent contre nous, il y a un intrus parmi nous. Si le monde va mal c’est à cause des juifs, à cause des banques juives. C’est une théorie de la conspiration.

Mais dans le roman Soumission, n’y-a-t-il pas une théorie de la conspiration, l’idée qu’une “grande substitution” est à l’œuvre, que les musulmans sont en voie de s’emparer du pouvoir ?

Je ne connais pas bien cette théorie de “la grande substitution”, mais j’accepte qu’elle ait une relation avec la race. Alors que mon livre ne parle pas d’immigration. Ce n’est pas le thème.

Ce n’est pas nécessairement racial, cela peut être religieux. Dans ce cas, votre livre décrit le remplacement du catholicisme par l’Islam.

Non. Mon livre décrit la destruction de la philosophie héritée des lumières, qui n’a plus de sens pour personne, ou seulement pour une poignée. Le catholicisme cependant, ne va pas mal du tout. Je maintiens qu’une alliance entre les catholiques et les musulmans est possible. On l’a déjà vu dans le passé. Cela pourrait se répéter.

Vous êtes devenu agnostique. Pouvez-vous observer ce qui se passe avec plaisir et voir comment est détruite la philosophie des Lumières?

Oui. Cela doit arriver un jour ou l’autre et il se pourrait bien que ce soit maintenant. En ce sens aussi je suis Comtien. Nous nous trouvons dans ce qu’il appelait l’étape métaphysique, laquelle a commencé au Moyen Âge, et son émergence a détruit la phase précédente. En elle même, la philosophie des Lumières ne peut rien produire, uniquement du vide et du malheur. De telle sorte que oui, je suis hostile à la philosophie des lumières, cela doit être bien clair.

Pourquoi avez-vous choisi le monde universitaire comme cadre de votre roman? Parce qu’il incarne les Lumières ?

Je ne sais pas vraiment. La vérité est que je voulais qu’il existât une seconde histoire dans l’histoire, assez importante, et qui se pencherait sur Huysmans. Ainsi m’est venue l’idée de mettre en scène un universitaire.

Vous saviez, depuis le début, que vous écririez ce roman à la première personne ?

Oui, parce que c’était un jeu avec Huysmans. Il en fut ainsi depuis le début.

Une nouvelle fois, vous avez mis en scène un personnage qui est en partie un autoportrait. Pas totalement, bien sûr, mais on trouve par exemple la mort de vos parents.

Oui, j’ai utilisé certains éléments, quoique les détails soient très différents. Mes personnages principaux ne sont jamais des autoportraits, mais toujours des projections. Par exemple : Si j’avais lu Huysmans jeune, et que j’eusse étudié la littérature et choisi la carrière de professeur? J’imagine des vies que je n’ai pas vécu.

Tout en permettant que des faits réels s’insèrent dans les vies fictives.

.J’utilise des faits qui m’ont affecté dans la vie réelle, oui. Mais chaque fois je les transpose. Dans ce livre, ce qui reste de la réalité est l’élément théorique (la mort du père) mais tous les détails sont différents. Mon père était très différent du personnage du roman, sa mort n’est pas du tout survenue ainsi. La vie me donne seulement les idées de base.

En écrivant ce roman avez-vous eu la sensation d’être une Cassandre, un prophète de la catastrophe?

Réellement, ce livre ne peut être décrit comme étant une prédiction pessimiste. A la fin, les choses ne se terminent réellement pas si mal.

Elles ne se terminent pas si mal pour les hommes, mais pas pour les femmes.

Oui, c’est un problème très différent. Cependant, je considère que le projet de reconstruire l’Empire romain n’est pas si stupide ; si cela réoriente l’Europe vers le Sud alors tout commence à acquérir un certain sens, même si en ce moment il n’y en a aucun. Politiquement, on peut même se réjouir de ce changement ; en réalité il n’y a aucune catastrophe.

Cependant le roman apparaît particulièrement triste.

Oui, il y a une profonde tristesse sous-jacente. Mon opinion est que l’ambiguïté culmine dans la dernière phrase “il n’y aurait aucune raison pour garder le deuil”. En réalité, on pourrait terminer le livre en ressentant exactement le contraire. Le personnage a deux bonnes raisons pour garder le deuil : Myriam et la Vierge Noire. Mais finalement il ne les regrette pas. Le roman baigne dans la tristesse sous la forme d’une ambiance de résignation.

Comment situez-vous ce roman par rapport à vos autres livres ?

On pourrait dire que j’ai réalisé des choses que je voulais faire depuis longtemps, des choses que je n’avais jamais réalisées avant. Par exemple, mettre en scène un personnage très important que jamais personne ne voit, comme Ben Abbes. Aussi, il me paraît que la fin de l’histoire d’amour est la plus triste que j’aie jamais écrite, quoique ce soit la plus banale : les yeux ne voient plus, le cœur ne sent plus rien. Ils avaient des sentiments. De manière générale, la sensation d’entropie est beaucoup plus forte que dans mes autres livres. On y trouve un côté sombre, crépusculaire qui explique la tristesse du ton. Par exemple, si le catholicisme ne fonctionne plus c’est parce qu’il a porté tous ses fruits, et paraît désormais lié au passé ; il s’est vaincu lui même. L’islam est une image du futur. Pourquoi l’idée de Nation s’est-elle épuisée? Parce qu’on a abusé d’elle durant trop de temps.

On ne trouve là aucun trait de romantisme, et encore moins de lyrisme. Nous sommes entrés en décadence.

C’est exact. Le fait d’avoir commencé avec Huysmans doit avoir une relation avec cela. Huysmans ne pouvait pas revenir au romantisme, mais il lui restait la possibilité de se convertir au catholicisme. Le point de contact le plus clair avec mes autres livres est que la religion, quelle qu’elle soit, est nécessaire. Cette idée apparaît dans beaucoup de mes livres. Dans celui-ci aussi sauf que cette fois il s’agit d’une religion existante.

Quelle est la place de l’humour dans ce livre ?

On trouve des personnages comiques par-ci par-là. Je dirais qu’en réalité c’est comme d’habitude, on y trouve le même nombre de personnages ridicules.

Nous n’avons pas beaucoup parlé des femmes. Une de fois de plus, vous serez critiqué sur ce point.

Evidemment, le livre ne plaira pas à une féministe. Mais je ne peux rien y faire.

Cependant, vous fûtes surpris que les lecteurs eussent qualifié de misogyne “Extension du domaine de la lutte”. Votre nouveau roman ne va pas améliorer les choses.

Je continue de penser que je ne suis pas misogyne. De toutes manières, je dirais que cela n’a aucune importance. Il se peut cependant que les gens ne soient pas content de ma démonstration, puisque je montre que le féminisme est condamné par la démographie. De sorte que l’idée sous-jacente, qui pourrait vraiment déplaire, est que l’idéologie importe peu face à la démographie.

Ce livre ne prétend donc pas être une provocation ?

Il accélère l’histoire; mais non, on ne peut pas dire qu’il soit une provocation, si ce terme signifie que l’on dit des choses considérées comme incertaines seulement pour énerver les gens. Je condense une évolution qui me paraît réaliste.

Pendant que vous écriviez ou relisiez le livre, avez-vous anticipé quelques réactions possibles lors de sa publication ?

Je suis totalement incapable de prévoir ces choses là.

Certains pourraient être surpris de votre nouvelle orientation puisque le livre précédent fut accueilli triomphalement ce qui réduisit au silence vos critiques.

La réponse correcte est que, franchement, je ne l’ai pas choisie. Le livre commença avec une conversion au catholicisme qui eut dû se faire mais ne se fit pas.

N’y-a-t-il pas quelque chose de désespéré dans ce processus, que vous n’avez pas réellement choisi?

Le désespoir provient du fait que l’on abandonne une civilisation très ancienne. Mais finalement le Coran me semble meilleur que ce que je pensais, maintenant que je l’ai relu - ou plutôt lu - La conclusion évidente est que les djihadistes sont de mauvais musulmans. Obligatoirement, comme dans tout livre religieux, une certaine latitude est laissée à l’interprétation. Mais une lecture honnête devrait conclure qu’en général l’agression par la guerre sainte n’est pas approuvée, seule la prière est valide. On peut donc dire que j’ai changé d’opinion. Pour cela je ne sens pas que j’écris à partir d’une peur. Je sens plutôt que l’on peut se préparer peu à peu. Les féministes ne pourront pas le faire, s’il faut absolument être honnête. Mais moi et beaucoup d’autres si, nous pourrons.

On pourrait remplacer le mot féministes pour celui de femmes, non ?

Non, on ne peut pas remplacer le mot féministes par celui de femmes. Vraiment pas. Je montre clairement que les femmes aussi peuvent se convertir.

Texte traduit par notre collaborateur Auran Derien

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

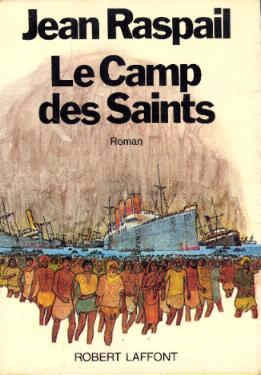

Quoi qu’il en soit, Houellebecq a le vent en poupe et l’on peut gager qu’il pulvérisera les ventes de début d’année. Il ne s’inscrit pas moins à la suite d’auteurs précurseurs comme Jean Raspail, lui-même empruntant, avec son prophétique et magistral Camp des saints, la dimension proprement visionnaire d’un Jules Verne au XIXe siècle ou d’un Anthony Burgess avec son Orange mécanique au XXe siècle.

Quoi qu’il en soit, Houellebecq a le vent en poupe et l’on peut gager qu’il pulvérisera les ventes de début d’année. Il ne s’inscrit pas moins à la suite d’auteurs précurseurs comme Jean Raspail, lui-même empruntant, avec son prophétique et magistral Camp des saints, la dimension proprement visionnaire d’un Jules Verne au XIXe siècle ou d’un Anthony Burgess avec son Orange mécanique au XXe siècle.

It is my opinion that

It is my opinion that